Cardiac amyloidosis becoming less rare thanks to nuclear medicine studies

Cardiac amyloidosis (CA)—a condition that causes the heart to become stiff due to amyloid deposits—is considered rare, but its diagnosis has become more common in recent years. A new study in the Journal of Nuclear Medicine offers insight into how the condition affects the general population, as well as how radiologists can help in the CA diagnostic journey [1].

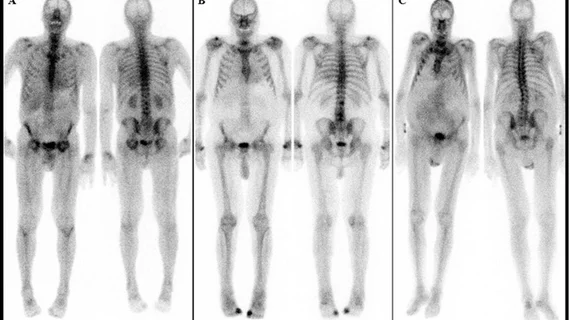

The study focused on patients who underwent nuclear medicine bone scans between 2010 and 2020 at the Medical University of Vienna in Austria. Out of 11,527 patients, 3.3% showed some level of uptake of the cardiac radiotracer commonly referred to as DPD (99mTc-3,3-diphosphono-1,2-propanodicarboxylic-acid). DPD uptake, whether discovered incidentally or otherwise, can be indicative of cardiac amyloidosis, Christian Nitsche, MD, PhD, of the Medical University of Vienna in Austria and colleagues explained.

“Patients undergoing bone scintigraphy (a nuclear medicine bone scan) may present with high levels of cardiac radiotracer (known as DPD) uptake as an incidental finding, which point to the presence of cardiac amyloidosis,” the experts wrote. “In this large-scale study we sought to estimate the prevalence of cardiac amyloidosis in the general population based on bone scans and to investigate the associated outcomes.”

To give the experts a better idea of how CA might affect the general population, they included patients referred to imaging for both cardiac and non-cardiac reasons. Nuclear medicine professionals analyzed and graded the patients’ scans from 0 to 3, with 0 signaling no DPD uptake and 2/3 representing confirmed cardiac amyloidosis.

The experts found that 1 in 50 patients referred for non-cardiac reasons displayed some level of DPD uptake, while the same was true for 1 in 5 of the cardiac referrals. When the researchers reviewed follow-up data (median follow-up was six years) on the patients, they found that nearly 30% of them had died. Additionally, 1.5% of patients had been hospitalized for heart failure during the follow-up period, with those having grade-2/3 DPD uptake having a 3.5 times higher risk of hospitalization in comparison to grade-0 subjects.

Cardiologist Andreas Kammerlander, MD, PhD, who was also involved in the research, suggested that “efforts should be maximized” to more reliably diagnose DPD uptake, and that when these findings are identified, it should be noted so that patients can be referred to cardiac specialists to initiate treatments.

To view the study abstract, click here.