Heading a soccer ball linked to reduced brain function

Heading a soccer ball looks safe to do, but what effect does it have on the brain over a two year period? Research presented at the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) conference in Chicago may have an answer.

According to RSNA, previous research has examined the immediate effect of hitting a soccer ball with your head, but little is known about the lasting impact of the technique.

“There is enormous worldwide concern for brain injury in general and in the potential for soccer heading to cause long-term adverse brain effects in particular,” senior author of the study Michael Lipton, MD, PhD, from Columbia University’s Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons said in an announcement from RSNA. “A large part of this concern relates to the potential for changes in young adulthood to confer risk for neurodegeneration and dementia later in life.”

For their research, Lipton and his colleagues developed a specialized questionnaire to determine how often players hit a soccer ball with their heads. Nearly 150 adult players (mean age of 27) were surveyed, the majority of whom were men (74%).

Exposure to heading over a two-year period was categorized as low, moderate or high based on a series of questions about how often an individual plays in actual games, practices soccer and ultimately heads the ball.

“When we first started, there was no method for assessing the number of head impacts a player experienced,” Lipton added. “So, we developed a structured, epidemiological questionnaire that has been validated in multiple studies.”

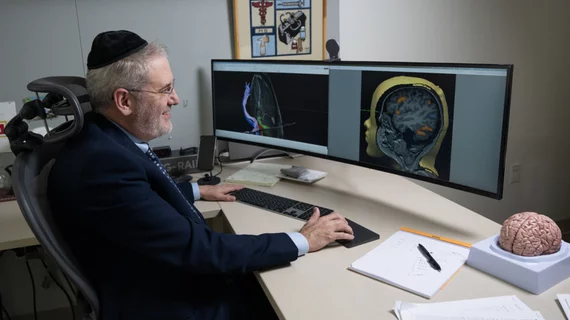

The participants underwent evaluations for verbal learning and memory, along with diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) using MRI techniques, both at enrollment and after the two-year window. DTI was used to categorize the microstructure of the brain by monitoring the microscopic movement of water molecules within the tissue.

In comparison to the initial test results, the group with a high frequency of heading—more than 1,500 headers in two years—exhibited an augmentation of diffusivity in frontal white matter regions. Additionally, there was a reduction in the orientation dispersion index in specific brain regions following two years of exposure to heading.

“Our analysis found that high levels of heading over the two-year period were associated with changes in brain microstructure similar to findings seen in mild traumatic brain injuries,” Lipton explained. “High levels of heading were also associated with a decline in verbal learning performance. This is the first study to show a change of brain structure over the long term related to subconcussive head impacts in soccer.”

The analysis accounted for variables such as age, sex, education and concussion history.

Reduced brain function is also seen at 12 months

A second study, conducted by a different research team that also included Lipton, analyzed heading a soccer ball over a 12 month period, assessing potential brain damage in 353 amateur players between the ages of 18 and 53 (73% male). Unlike previous research that focused on deep white matter regions exclusively, this study aimed to assess the integrity of the interface between the brain's gray and white matter in proximity to the skull.

“Importantly, our new approach addresses a brain region that is susceptible to injury but has been neglected due to limitations of existing methods,” Dr. Lipton said of the second study. “Application of this technique has potential to disclose the extent of injury from repetitive heading, but also from concussion and traumatic brain injury to an extent not previously possible.”

Once again, the results showed there is some reduced brain function associated with heading a soccer ball. The researchers found that the normally sharp gray matter-white matter interface was blunted, and the level of blunting correlated to how often a player headed a ball.

“We used DTI to assess the sharpness of the transition from gray matter to white matter,” Lipton said. “In various brain disorders, what is typically a sharp distinction between these two brain tissues becomes a more gradual, or fuzzier transition.”

Lipton added that gray matter-white matter interface integrity plays an important role in cognitive performance, including the formatting of speech. He hopes this new research will add weight to the ongoing debate about brain damage risk in soccer.

“These findings add to the ongoing conversation and contentious debate as to whether soccer heading is benign or confers significant risk,” Lipton concluded.