Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography helps predict the risk of negative outcomes after a liver transplant

Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography is a safe and effective tool for predicting poor outcomes following a liver transplant, according to a new pilot study.

Programs are increasingly relying on deceased donors to help treat patients with late-stage liver disease. These donors, however, require alternate management strategies to ensure lifesaving organs are in the best possible condition for recipients, researchers explained Monday in the European Journal of Radiology.

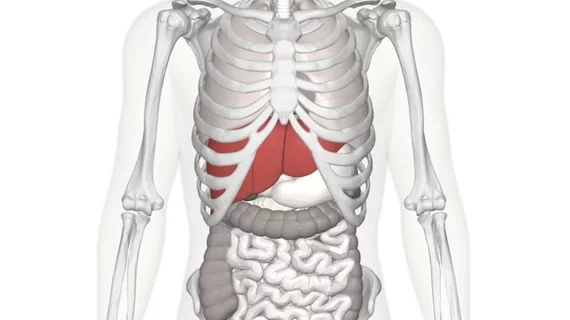

And assessing liver function via imaging may help predict a patient’s risk of developing primary graft dysfunction (PGD), a severe injury that occurs within 72 hours of transplant, commonly resulting in early death.

“For potential donors with unstable vital signs in the intensive care unit, finding a safe and noninvasive method to monitor liver perfusion is of clinical importance,” Bo-wen Zheng, with the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University’s Department of Medical Ultrasonics in China, and colleagues explained. “Having a clear understanding of donor factors can improve recipient selection, organ allocation and, potentially, patient and graft survival,” they added later.

The group set out to specifically assess whether Doppler ultrasonography (DUS) and contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS) could determine if liver donation after brain death and cardiac death increases a patient's risk of developing short-term primary graft dysfunction and other long-term complications.

Zheng et al. included 52 consecutive donor livers that underwent DUS/CEUS exams before being surgically removed between February 2016 and June 2018. Two radiologists analyzed the clinical images.

Among the overall total, 20 liver recipients developed PGD. Further analysis revealed a decrease in CEUS enhancement to be an independent risk factor for poor short-term outcomes. The researchers did not find any imaging factors independently associated with long-term complications. All exams were well-tolerated, the authors noted.

This research would benefit from a larger sample size, the authors explained, as well as an investigation into interobserver agreement. But their findings do have real-world implications.

“In summary, the decrease in enhancement on CEUS, indicating hemodynamic changes in DBD and DCD donor livers, is an independent risk factor for poor short-term outcomes of LT,” Zheng and colleagues wrote. “CEUS can be applied as a promising predictive tool for donor livers to evaluate perfusion effectively and safely.”