Size matters when it comes to neuroimaging studies

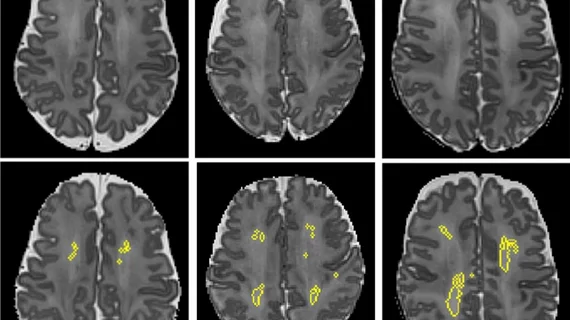

Although research that utilizes MRI has uncovered many structural and functional correlations between our brains and various diseases and illnesses, new research suggests that many neuroimaging studies are ineffective due to their sample sizes.

In recent years, the study of mental illnesses and other neurological conditions has benefited greatly from the use of MRI brain scans. Functional MRI (fMRI), for example, has allowed scientists to map specific structures and functions of the brain in real time, revealing clues about how patients’ conditions and behaviors could be associated with neurological changes observed on imaging.

While these scans have offered a plethora of insight into the inner workings of the brain, the information obtained from neuroimaging research has yet to translate widely into realistic advances of treatment options, especially in the realm of mental health. A study published recently in Nature explains why.

“A primary challenge has been replicating associations between inter-individual differences in brain structure or function and complex cognitive or mental health phenotypes (brain-wide association studies (BWAS)),” first author Scott Marek, PhD, with the department of psychiatry at Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis, and co-authors disclosed. “Such BWAS have typically relied on sample sizes appropriate for classical brain mapping, but potentially too small for capturing reproducible brain-behavioral phenotype associations.”

To measure how sample sizes of brain-wide association studies might impact the reliability of their findings, researchers analyzed the three largest neuroimaging datasets currently available—the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study (11,874 participants), the Human Connectome Project (1,200 participants) and the UK Biobank (35,375 participants)—to examine the reproducibility of results highlighted in the research.

The authors revealed that the median neuroimaging sample size is around 25, which was much smaller than they anticipated. They described the research they analyzed as “underpowered” and explained that studies with inadequate sample sizes were resulting in frequent replication failures.

“As sample sizes grew into the thousands, replication rates began to improve and effect size inflation decreased,” the authors said.

Though the authors implied that many neuroimaging studies have been lacking in numbers, they maintained their optimism about the future of research, pointing to the availability of large datasets and data sharing across institutions, which enables scientists to conduct studies on a larger scale with reliable and reproducible results.

You can view the detailed research in Nature.

More on neuroimaging research:

MRI scans show COVID's 'significant' impact on the brain

MRI features uncover differences between the brains of autistic girls and boys

'Pandemic brain': PET/MRI images reveal how COVID's impact is felt by non-infected individuals

New advanced PET imaging reveals root of cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer's