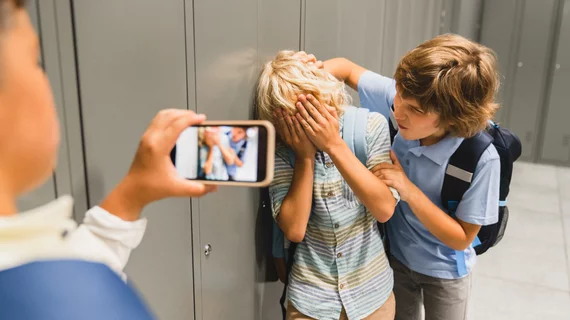

Bullied children are at risk of developing psychotic disorders

Researchers from the University of Tokyo turned to radiological imaging to get a better sense of what happens to the brains of adolescents who are victims of frequent bullying—and the results are alarming.

According to the study findings published in Molecular Psychiatry [1], young people who are bullied by their peers are at greater risk for episodes of psychosis, with their brains experiencing lower levels of a neurotransmitter glutamate responsible for regulating emotions. The authors, led by Naohiro Okada, MD, PhD, of the University of Tokyo’s International Research Center for Neurointelligence, said this chemical messenger in the brain plays a role in regulating impulse control and could serve as a target for treating psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia.

“Studying these subclinical psychotic experiences is important for us to understand the early stages of psychotic disorders and for identifying individuals who may be at increased risk for developing a clinical psychotic illness later on,” Okada said in a statement.

Okada and the other authors added that those who experience psychosis or who have schizophrenia are shown to have lower-than-normal levels of glutamate in the brain’s anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) region, responsible for regulating emotions and decision-making. This study is one of the first to show there is a potential causal link between bullying and lower levels of glutamate.

For the research, a cohort under 18 years of age had the ACC region of their brains examined with magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), which measures brain structure and function. The researchers measured glutamate levels at the time of the imaging and at later dates to assess progressive changes over time. Study participants were also surveyed on their level of bullying (none to severe) and the type (physical or verbal), as well as any interventions they received to help them cope.

While none of the subjects of the study had full episodes of psychosis, bullying was associated with subclinical psychotic experiences, meaning they showed symptoms without meeting the criteria for a psychotic disorder. Symptoms included abnormal behavior, paranoia, hallucinations, delusions, and incoherent speech—which are consistent with known negative outcomes of bullying, such as violence and suicide. Additionally, the researchers found that higher levels of these symptoms were associated with lower levels of glutamate in the ACC region.

Okada said interventions could improve outcomes and potentially stop a full blown psychotic state from emerging.

“First and foremost, anti-bullying programs in schools that focus on promoting positive social interactions and reducing aggressive behaviors are essential for their own sake and to reduce the risk of psychosis and its subclinical precursors,” he said. “These programs can help create a safe and supportive environment for all students, reducing the likelihood of bullying and its negative consequences.”

Despite identifying a potential target of pharmacological interventions, Okada said nonpharmacological interventions, such as therapy, could be enough to restore neurological balance.

The full study is available at the link below.