MRI, PET key to identifying 2 variants of Parkinson’s disease

Advanced MRI and PET imaging have helped confirm suspicions in neuroscience that Parkinson’s is more than one disease.

It’s precisely two, according to researchers who designed a study to separate disease types and now have had their work published in Brain.

The team, from Aarhus University and its affiliate hospital in Denmark, began with the hypothesis that Parkinson’s is either body-first or brain-first.

Body-first Parkinson’s, they theorized, starts in the intestines and spreads to the brain through neural connections, while brain-first Parkinson’s originates in the brain and metastasizes to the intestines as well as to other organs, including the heart.

The researchers also theorized that isolated REM sleep behavior disorder (iRBD) is a prodromal phenotype for the body-first variant.

Per Borghammer, PhD, Jacob Morsager, MD, and colleagues chose 37 consecutive de novo Parkinson’s patients for a case-control PET study. Of these, 24 patients were RBD-negative and 13 were RBD-positive. A comparator group comprised 22 iRBD patients.

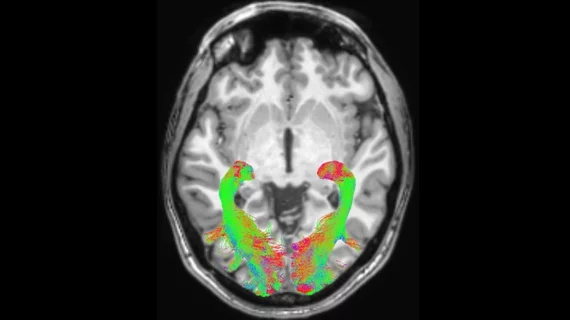

C-donepezil PET/CT was used to assess cholinergic (parasympathetic) innervation; I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy, to measure cardiac sympathetic innervation; neuromelanin-sensitive MRI, to measure the integrity of locus coeruleus pigmented neurons; and F-dihydroxyphenylalanine (FDOPA) PET to assess putaminal dopamine storage capacity.

CT scans were used with radiopaque markers to asses colon volume and transit times.

The researchers found that some patients had damage to the brain’s dopamine system before damage in the intestines and heart occurred. Scans of other patients revealed damage to the nervous systems of the intestines and heart before damage in the brain’s dopamine system was visible.

In a news release sent by the university, Borghammer comments that the results could be “very significant” for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease in the future, with care pathways picked to best address individual patients’ disease patterns.

Additionally, he says, the ability to identify the two types of Parkinson’s will enable researchers to better examine risk factors and possible genetic factors that pertain to each.

“We now have knowledge that offers hope for better and more targeted treatment of people who are affected by Parkinson’s disease in the future,” Borghammer adds.