CT reveals undersized lung airways as ‘major’ COPD risk factor, ‘on par’ with cigarette smoking

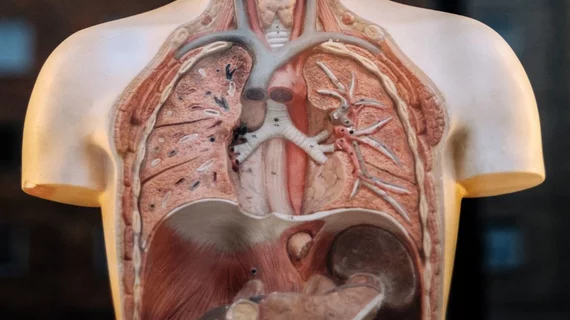

Computed tomography scans and personalized health data have revealed that having smaller airways relative to lung size is a significant risk factor for developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), nearly the same as smoking cigarettes.

The findings, published June 9 in JAMA, help explain why 1 in 4 cases of the lung disease that’s most commonly associated with smoking occurs in individuals who have never even picked up a cigarette. Measuring the condition—known as dysanapsis—has long eluded researchers, but is now a bit clearer thanks to advances in imaging.

"Our findings suggest that dysanapsis is a major COPD risk factor—on par with cigarette smoking," said Benjamin M. Smith, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. "Dysanapsis is believed to arise early in life. Understanding the biological basis of dysanapsis may one day lead to early life interventions to promote healthy and resilient lung development."

For their research, Smith and colleagues looked over health data—predominantly lung CT scans—from more than 6,500 older adults enrolled in three leading lung studies across the U.S. and Canada. In these participants, those with smaller airways relative to lung size had the poorest lung function and were eight times more likely to develop COPD.

The findings directly complement a “landmark” 2015 study revealing two major pathways toward late-in-life COPD. Traditionally, people with normal lung function quickly decline after years of smoking or air pollution.

"But there's a second pathway in people who have reduced lung function from an early age. This low starting point increases the risk for COPD in later years, even in the absence of rapid lung function decline," Smith, who is also the lead author of the study, noted. "Based on our data, dysanapsis may account for a large percentage of these cases."

In addition to those with abnormally small airways, the team found that a number of lifelong heavy smokers without COPD had larger than expected airways for their lung size.

Smith explained that these adults with abnormally sized pathways may be able to withstand “considerable” damage from cigarettes while avoiding the lung disease.