Study examines use of MSOT for detecting pancreatic cancer, improving surgery

Pancreatic cancer outcomes remain among the worst for patients, but researchers at the University of Oklahoma Health’s Stephenson Cancer Center hope to change that by improving early detection of the disease.

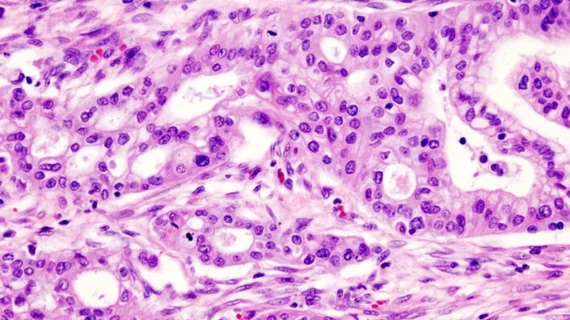

An upcoming study from the Stephenson Cancer Center will test a novel imaging technique that combines a specialized contrast agent designed to target pancreatic cancer cells with multispectral optoacoustic tomography (MSOT). This enables the detection of pancreatic cancer cells at a microscopic level—roughly 200 microns in size—significantly smaller than current methods, such as CT scans which can only detect tumors when they reach around a centimeter in size. Ideally, this advancement offers a tenfold increase in sensitivity, allowing for earlier and more accurate detection of pancreatic cancer cells.

“Pancreatic cancer is one of the hardest cancers to cure because it is difficult to detect cancer cells at the microscopic level,” lead researcher on the study Lacey McNally, PhD, from the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine said in a statement. “Because there are usually no early symptoms of pancreatic cancer, it is typically not diagnosed until after it has spread, and outcomes are very poor—about a 9% overall chance of survival. Surgery and chemotherapy offer the patients the best chance, but for surgery to work, we have to remove all the cancer, and that is difficult to do.”

MSOT is not new, but its use in medicine is only now being understood, which is why McNally and her team have earned a $3 million grant from the National Cancer Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), for this project.

For the study, McNally devised a contrast agent tailored for detecting pancreatic cancer cells. The agent is delivered via IV, and the dye reacts with uniquely acidic cells in the pancreas, effectively turning the dye on. The MSOT then delivers infrared light into the body, which stimulates the contrast agent, creating sound waves that are then converted into colors. The result is an image so detailed that it captures cancer cells that otherwise would evade detection from traditional imaging, thus improving early detection—at least, that’s the hope.

The technique may also be useful to help surgeons plan their approach by highlighting the full spread of the cancer, particularly around critical blood vessels near the pancreas. Additionally, the researchers believe MSOT could be useful in assessing the effectiveness of chemotherapy prior to surgery since it can effectively detect whether cancerous cells are still active.

This innovation has the potential to improve surgical outcomes—and given that pancreatic cancer disproportionately affects people over 60 who are at high-risk of surgical complications, MSOT could mean the difference between life and death.

“This is a hybrid approach that accomplishes what a CT cannot,” McNally added. “Pancreatic cancer often creates tentacles that spread out beyond the primary tumor. Currently, there is no way for the surgeon to know where they are. But if the surgery team can use this MSOT approach in the operating room, it can tell them in real time where the cancer has metastasized so they can remove it.”

The study is one of several the NIH is funding in 2024 to look deeper into the medical applications for MSOT, and the technique is presently being used in several clinical trials at University of Oklahoma Health.