Expert calls for education, research to spur adoption of intravascular ultrasound

Earlier this year, healthcare imaging company Philips brought attention to a new paper from a panel of experts on heart health and cardiac imaging calling for the wider adoption of intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), specifically for the identification of peripheral arterial disease.

The expert opinion was published in multiple medical journals. In it, the authors led by Eric A. Secemsky, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, noted that despite mounting evidence for its efficacy, adoption and use of IVUS remains low. In fact, many technologists and clinicians are not even trained to perform intravascular imaging.

Health Imaging spoke to Secemsky not only about the panel's recommendation for use of IVUS as a standard imaging procedure for peripheral arterial and deep venous diseases, but also to get a sense of how he thinks barriers to adoption can be overcome and what other applications exist for this underutilized imaging procedure.

Editor’s Note: The following has been modified for clarity and concision.

Health Imaging: In your own words, can you summarize what IVUS is?

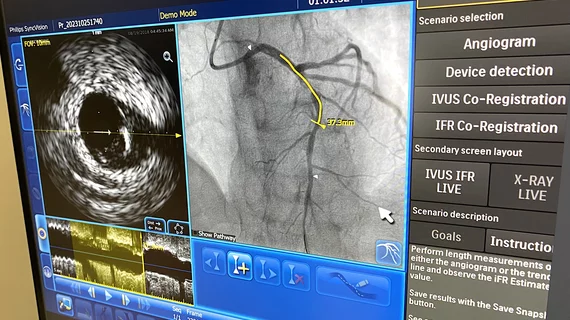

Secemsky: IVUS is intravascular ultrasound, and it’s a tool used within the blood vessel—so either an artery or a vein in the lumen of the vessel—and it uses ultrasound technology to capture an image of the vessel from the inside out. And then, by capturing this type of image, providers can get characteristics of the vessel that are not visible on images from an angiogram, CT scan or an MRI. IVUS allows us to see the wall of the inner surface of the vessel and any disease that might be hard to visualize on other imaging techniques, including an invasive angiogram.

What are the advantages of IVUS guided procedures for both staff and patients?

IVUS can be used to lower the amount of radiation that's necessary during the procedure. It could also lower the amount of exposure for patients to contrast medium—the medium that we inject during an angiogram to make the arteries and veins glow—and it could really help us better recognize and treat pathology when we might not have a clear understanding of what's going on, like in a case where there may be some guesswork filling in gaps, because invasive imaging is not completely clear. So, I think there are numerous benefits, from reducing radiation, reducing the time of the procedure and assuring that the procedure is done as well done as possible—all of that has implications for both staff and patients.

Can you summarize the recommendations from the joint expert opinion regarding the use of IVUS for peripheral arterial and deep venous interventions?

Yeah, there's been a growing recognition that IVUS can be used to help improve patient outcomes when undergoing treatment for artery disease or venous disease of the lower extremity. IVUS is minimally invasive; it goes through the same IV access site that we would use for a procedure to open up arteries or open up veins. It causes no harm to the patient and it gives extra data that allows the clinician to make a more informed decision.

In terms of our expert review document, there was clear consensus that we can be better physicians, better clinicians, better operators if we combine the use of invasive angiography and biography with this minimally invasive safe IVUS catheter. So, the meat of the document was really us coming together to acknowledge the growing role of IVUS as an adjunctive to our procedures—minimally invasive procedures of the lower extremity—and then to really understand how do we disseminate this technology, help democratize it so others feel comfortable interpreting and analyzing the same data, and finding out how to best incorporate that data to help benefit the patient.

A statement on the joint opinion mentions that IVUS utilization remains low, despite growing clinical evidence. What do you believe to be the primary reasons for the low adoption rate?

IVUS for peripheral intervention has been around for a while, but really over the last few years interest in it has grown due to an increasing amount of evidence to support its use, in addition to the greater realization that we do have limitations with how we currently perform minimally invasive endovascular procedures. We've seen adverse events on the venous side with stent migration; we know the patency of arterial procedures needs to improve if we're going to compete with surgery. And so, I think now is the right time for people to understand that improving IVUS might be one way where we can be doing a better job as minimally invasive proceduralists.

But, the issue of growth is multifaceted. Again, we haven't had all the evidence that we've needed, but even when we do have a lot of evidence, we've seen slow growth. And this is how it's played out in the coronary intervention side, where there are many trials supporting IVUS during coronary intervention, yet adoption rates remain low. Why? A lot of people didn't have IVUS training during their fellowships or residencies, and so trying to pick up a new device, understand how to make it work, believing that it adds value, believing that it doesn't add time to the procedure is a challenge.

On top of that, outside of the U.S. there's very little reimbursement for intravascular imaging. So, when you use the catheter, it comes at a loss to an institution. Even in the US, there's some challenges with reimbursement. And so I think we all use technology that we feel won't break the bank and we have to weigh that with the hospital all the time. But if we all are in agreement that this technology could help patients, help staff—help operators be better operators—then we need to support it with the reimbursement necessary to allow free use of IVUS when it is needed.

In terms of the evidence, did the panel focus on pushing the adoption of IVUS for peripheral artery intervention because that’s where the data is the strongest?

I think everybody acknowledged that IVUS can be used, at least selectively, to improve outcomes for peripheral artery intervention, but the main question was how do we create a strategic algorithm to ensure it's being used appropriately? Again, we want to be able to say, if someone encounters a type of lesion or dissection, everybody—if they use IVUS—is going to treat it the same way and understand what to do next. We’re not there yet in terms of specific protocols; I think we've left people with half of the information they need to be good operators. A lot of us who are doing this with repetition, we developed these standards over time, but it's hard to get new users to adopt them, especially with a technology they may not be too familiar with.

So, I think the one area that we really wanted to focus on in terms of data evidence is generating algorithmic approaches for an indeterminate severity lesion or a dissection of unclear significance. We need to really be able to treat these similarly across the world, and we’re working to do that.

The need for more research and education is a barrier to adoption. For example, there is an assumption that procedure time is added with IVUS, and we're working on studies to demonstrate that the workflows that support the use of IVUS do not necessarily add additional procedure time. We're also mindful of how we create educational opportunities that can prospectively be evaluated to build comfort with intravascular imaging—and that is all ongoing. We're always looking for more prospective data with long-term outcomes, but also there's smaller stuff, like time barriers and educational needs, that remain at the top of the list.

How do you envision the future of IVUS technology, and will we get to a point where it’s integrated into clinical guidelines as a standard practice?

IVUS at this point is not going anywhere. It is clear from this document we wrote that, whether it’s selective use or more routine, it's going to remain an important tool in everybody's practice. The majority of people actually have IVUS available now in their suites, whether it's a hospital or outpatient center. It's just a matter of how they're using it and how frequently.

So, I think the future of IVUS is very strong and use will only increase but, again, everything needs to be done responsibly. If there are clear demonstrated benefits for routine use, then we need to help people see that benefit and get there. And if people want to use it more selectively, they still need to understand the tool for when they do use it.

Regardless, I think that as we move forward, relying only on a radiation contrast dependent modality like angiography has limitations—a 2D picture is from a time in the past. We're going to see more and more adjunctive technology, like IVUS, help us get better outcomes and to treat our patients more optimally over the long-term.