Abnormal CT findings increasingly common among countertop workers

People who are involved in the manufacturing of certain countertops may be at risk of developing long-term pulmonary complications, according to new research presented at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America.

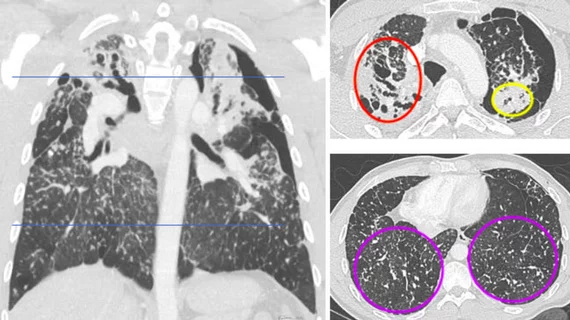

Experts have found that individuals who work with engineered stone countertops are increasingly being diagnosed with silicosis—a chronic lung condition that is the result of inhaling large amounts of silica dust, which is naturally present in sand, quartz and many different types of stone. Silicosis is a type of pulmonary fibrosis and can lead to permanent lung damage and even death if left untreated.

“This is a new and emerging epidemic, and we must increase awareness of this disease process so we can avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment for our patients,” lead author of the new study Sundus Lateef, MD, a diagnostic radiology resident at the University of California in Los Angeles, said in a release on the findings.

Although silicosis is a known hazard of working in certain construction settings, there has been an abnormal uptick of diagnoses in recent years. This could be due, in part, to the growing demand for quartz countertops, which are known to require less maintenance, but contain significantly more crystalline silica than natural stone.

Lateef and colleagues conducted an analysis that included chest radiographs, CT scans and pulmonary function tests on 55 countertop workers at a large hospital where silicosis cases were historically rare. Since silicosis is an uncommon diagnosis, the team wanted to determine whether patients presenting with symptoms showed any indication of the disease on imaging prior to their actual diagnosis.

Primary clinicians recognized silicosis at the initial encounter in only four of 21 cases (19%), while radiologists recognized it in seven of 21 cases (33%). Alternative diagnoses, such as infection, were initially suggested in most cases. Nearly half of the patients (48%) had atypical imaging features—a finding that warrants attention, Lateef cautioned.

“Silicosis may present with atypical features that may catch radiologists off guard in practice regions where silicosis is not traditionally diagnosed, which can lead to delays in diagnosis,” Lateef said. “There is a critical lack of recognition of exposure and screening for workers in the engineered stone manufacturing industry.”

Lateef suggested that more stringent screening and greater awareness of abnormal image findings among these workers could improve outcomes. He and his colleagues are working with the state to improve working conditions and screening for workers who are routinely exposed to silica dust.