New brain imaging study challenges conventional treatment of schizophrenia

New research published in The American Journal of Psychiatry suggests the brain function of individuals with schizophrenia is more nuanced than previously thought.

The results, published Jan. 4, found the social brain function of patients with the mental illness are not unconditionally different from those without it, but fall into sub-groups that can respond to different methods of treatment. Researchers say their findings challenge traditional diagnostic categories.

“We know that, on average, people with schizophrenia have more social impairment than people in the general population," said senior author Aristotle Voineskos, MD, with the Center for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, in a prepared statement. "But we needed to take an agnostic approach and let the data tell us what the brain-behavioral profiles of our study participants looked like. It turned out that the relationship between brain function and social behavior had nothing to do with conventional diagnostic categories in the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders)."

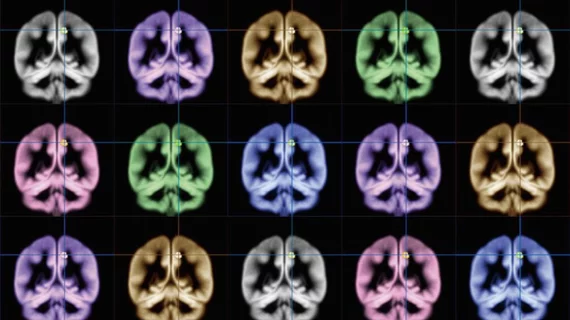

Voineskos and colleagues recruited 179 participants (109 with schizophrenia spectrum disorder and 70 controls) from CAMH, Zucker Hillside Hospital in New York and the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center in Baltimore. All were asked to imitate the emotions of faces, which reflected their ability to interact socially, while undergoing a brain fMRI scan.

Three different “activation profiles” were found: Typical, over-activated and de-activated profiles. Importantly, the profile distinction was not related to diagnosis or scan site.

The authors wrote that those with over-activated networks may need to work harder to compete the same task, while the de-activated group appeared to have efficient use of their brain during the task.

To confirm their findings the team repeated the study on a separate sample of 108 patients and found the same three profiles.

"There is really no effective treatment to deal with these social impairments, which is why we're really invested in figuring out the brain networks of social behaviors as targets for treatment and research," said Anil Malhotra, MD, of Zucker Hillside Hospital, in the same statement. "We are now positioned to test treatments to help change brain function, rather than focusing on symptoms alone, when it comes to helping people with social impairment."