Radiologists identify second type of schizophrenia, challenging conventional knowledge

A team of radiologists from Penn Medicine has discovered a new type of schizophrenia, according to a recent study published in Brain. These patients have brain tissue volumes similar to healthy individuals, and may require a revised treatment approach.

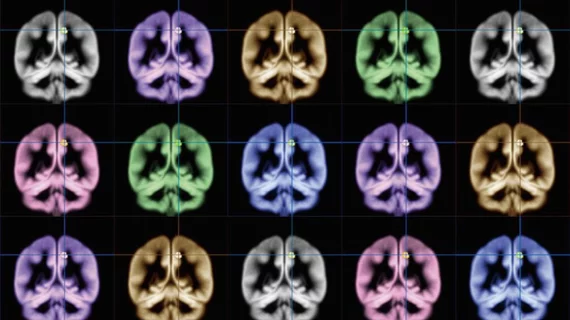

The discovery came after researchers combed through hundreds of brain scans and found that nearly 40% of patients did not have the reduced gray matter volumes typically seen in those with schizophrenia. Their new insights could provide clinicians with the nuanced information they need to personalize treatment for patients with this mental disorder, lead investigator Christos Davatzikos, PhD, said in a statement.

“Numerous other studies have shown that people with schizophrenia have significantly smaller volumes of brain tissue than healthy controls. However, for at least a third of patients we looked at, this was not the case at all—their brains were almost completely normal,” said Davatzikos, a professor of radiology at Penn’s school of medicine. “In the future, we’re not going to be saying ‘this patient has schizophrenia,’ we’re going to be saying ‘this patient has this subtype’ or ‘this abnormal pattern,’ rather than having a wide umbrella under which everyone is categorized.”

In an effort to look into this “poorly understood” disorder, Davatzikos and colleagues created a research consortium spanning the United States, China and Germany. In total, the international study group included 307 patients with schizophrenia and 364 healthy individuals; each person was 45 years old or younger.

The researchers then used a machine learning approach to identify “true disease subtypes” in the cohort’s brain scans. Davatzikos said their algorithm limits the influence of variables such as imaging protocols, age, sex and other factors. They determined that 115 patients with schizophrenia did not have the reduced gray matter volume normally seen in those with the disorder. It was rather the opposite; their brains revealed increased brain volumes in the middle region of the organ—known as the striatum—which plays a crucial role in voluntary movement.

Even after controlling for a number of factors such as differences in medication and age, the group could not determine a solid reason for this finding. They also did not want to speculate as to why a number of patients with schizophrenia have brains similar to healthy patients.

“This is where we are puzzled right now,” Davatzikos said. “We don’t know. What we do know is that studies that are putting all schizophrenia patients in one group, when seeking associations with response to treatment or clinical measures, might not be using the best approach.”

Future work will address these shortcomings and offer a more detailed understanding of the newfound schizophrenia subtypes.