Some long COVID patients continue to display multi-organ damage one year after recovery

New research details how long COVID affects multiple organs in the body, revealing that people continue to display organ damage on imaging years after their initial infection [1].

In a study cohort of 536 long COVID patients, multi-organ MRI scans identified organ impairment in 62% of participants six months after their initial diagnosis; 29% of these individuals continued to display damage in at least one organ 12 months after being diagnosed with COVID.

Concerningly, healthcare workers affected by lingering symptoms accounted for a significant portion of study participants. For some of those workers, persistent symptoms like breathlessness, fatigue and cognitive dysfunction inhibited their quality of life and ability to perform their job.

The study’s corresponding author, Amitava Banerjee, Professor of Clinical Data Science at the UCL Institute of Health Informatics in the United Kingdom, noted that persistent symptoms and organ damage in anyone is of concern for clinicians, but additional implications are associated with organ impairment in healthcare workers.

“Impact on quality of life and time off work, particularly in healthcare workers, is a major concern for individuals, health systems and economies,” Banerjee noted.

Healthcare workers, many of whom reported no prior health conditions or illnesses, accounted for 32% of the study’s participants. Of these 172 individuals, 19 were still dealing with severe symptoms requiring them to remain out of work at a median follow-up of 180 days. Of note, these symptoms were most common in younger females.

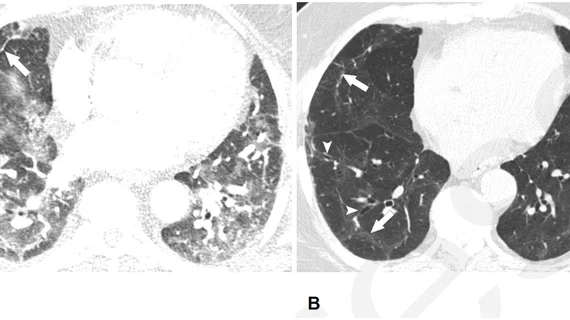

On baseline imaging, liver steatosis, kidney fibro-inflammation and splenomegaly were the most common findings, with healthcare workers having higher rates of liver impairment.

At the 12-month mark, despite continued signs of organ damage, many patients reported a reduction in their symptoms. Breathlessness decreased from 38% to 30%, cognitive dysfunction from 48% to 38% and overall poor health-related quality of life from 57% to 45%.

Despite this reduction, the experts indicated that participants' reported symptoms, imaging data and lab work did not provide a clear trajectory for long COVID recovery. As long as this remains unclear, the authors suggested that there will continue to be a need for multi-system investigations on larger cohorts of individuals.

The study abstract is available in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine.