Brain imaging debunks traditional theory about dyslexia

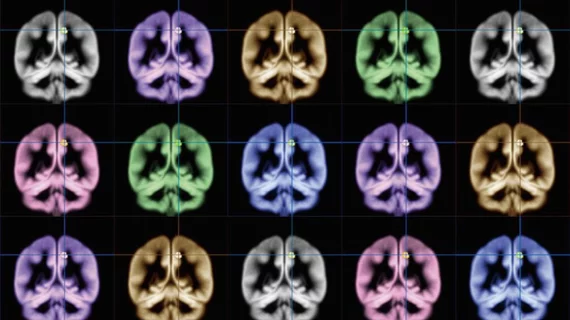

New research utilizing functional MRI (fMRI) has cast doubts on a commonly believed theory about dyslexia, potentially paving the way for new approaches to the learning disorder.

The cerebellum has long been thought to play a role in developmental of dyslexia, but this “cerebellar deficit hypothesis” has also been fraught with controversy, according to neuroscientists from Georgetown University Medical Center. The findings, published Oct. 9 in Human Brain Mapping, showed that not only is the cerebellum disengaged during reading in “typical readers,” but does not differ in kids with dyslexia.

“Prior imaging research on reading in dyslexia had not found much support for this theory called the cerebellar deficit hypothesis of dyslexia, but these studies tended to focus on the cortex,” first author, Sikoya Ashburn, a Georgetown PhD candidate in neuroscience, said in a statement. “Therefore, we tackled the question by specifically examining the cerebellum in more detail.”

Sikoya and colleagues used fMRI and a single word-processing task to assess differences in activity and connectivity in the brains of 23 children with dyslexia and 23 without the condition.

The team found brain regions in the cortex—typically proven to activate during reading—were not “communicating” with the cerebellum in kids with or without dyslexia when the brain was processing words. And when observing communication between brain regions at rest, Sikoya et al. found the cerebellum communicated “more strongly” in kids with dyslexia.

“These differences are consistent with the widely distributed neurobiological alterations that are associated with dyslexia, but not all of them are likely to be causal to the reading difficulties,” Ashburn said.

Going forward, the authors suggested their findings may help educate parents on which treatment programs may best benefit children struggling with the reading disorder.