Brain imaging pinpoints weaker ‘neural suppression’ in patients with autism

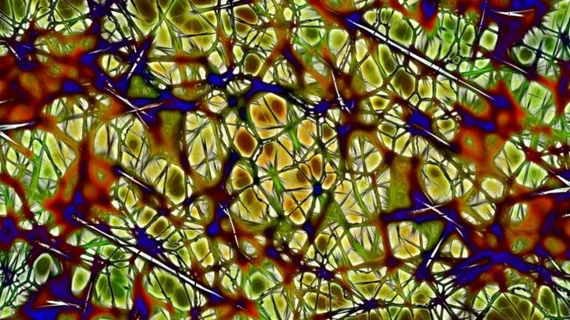

Researchers from the University of Minnesota Medical School have used functional MRI to show that the differences in sensory hypersensitivity among patients with autism spectrum disorder are associated with weaker neural suppression in a key area of the brain.

Neuroscience and psychiatry experts recognize that variances in sensory functioning are common among those with ASD, but until now researchers did not understand what was going on in the brain on a neural level to cause these differences.

The findings, published May 29 in Nature Communications, may help clinicians develop new screening mechanisms to identify children who are at risk for ASD and similar conditions.

"Our work suggests that there may be differences in how people with ASD focus their attention on objects in the visual world that could explain the difference in neural responses we are seeing and may be linked to symptoms like sensory hypersensitivity," Michael-Paul Schallmo, PhD, with U of M Medical School’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, said in a statement.

Schallmo, along with collaborators at the University of Washington in Seattle, enrolled 28 young adults with ASD and a comparison group of 35 neurotypical participants for their research. The team had participants complete visual tasks and used both fMRI and MR spectroscopy to gather data on brain activity.

They noted three distinct findings:

- Those with ASD had enhanced perception of large moving stimuli compared to patients in the control group.

- Brain responses to these stimuli varied among the 28 patients with ASD, and responses in the visual cortex showed “less neural suppression.”

- A “computational model” of abnormal neural processing in autism patients should be able to accurately describe the differences in brain responses.

Schallmo and colleagues added that their research may also help identify new targets to treat sensory symptoms of many brain development disorders.

In fact, the team is already working on a follow-up study of visual and cognitive functioning in young patients with ASD, Tourette syndrome, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder.