'Highly significant' MRI findings link hyperthyroidism to structural brain abnormalities

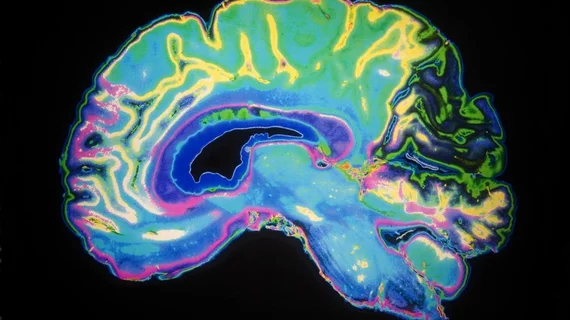

MRI brain scans recently revealed “highly significant” findings on how an imbalance in thyroid hormones affects brain function in patients with Graves' Disease (GD).

GD is a common cause of hyperthyroidism, a condition in which an excess of thyroid hormones are produced. Many patients with GD are known to suffer from fatigue, tachycardia, reduced tolerance to stress, anxiety, depression and other cognitive impairments.

It has been known for some time that GD manifests physically and mentally, with studies often blaming the side effects on abnormal hormone levels. When researchers took a different approach by using MRI to examine the impact of GD on the brain, their findings revealed that the link between physiological brain changes and hyperthyroidism is much more significant than previously thought.

The study, published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, examined the cases of 62 women who had recently been diagnosed with GD. The participants underwent an extensive evaluation of mental symptoms, a brain MRI and treatment for hyperthyroidism. They followed up over a period of 15 months, and their results were compared to a control group with normal thyroid levels.

The researchers suspected that, like other pathologies that affect cognition, brains of the women with GD would also display structural abnormalities in the medial temporal lobe (MTL).

Before treatment when hormone levels were high, the MR images showed smaller MTL volumes in the brains of those with GD than in the control group. Once hormone levels were balanced, the MTL volumes returned to their normal size.

“The fact that we can now show that the brain is genuinely affected is highly significant for the future,” said Helena Filipsson Nyström, associate professor of endocrinology at the University of Gothenburg. “For decades, the patients in our group have testified that they don’t feel they’ve recovered, and we hope our study will provide further clues about what happens in the brain.”

The authors note that although their findings are significant, they do present many other questions about how hyperthyroidism affects the brain.

“It’s important for patients that research is underway in this area since it’s been neglected for so long. Second, it also results in new studies on what goes on in the brain in toxic goiter,” Filipsson Nyström said.